Review by Deborah Frontiera

As a long-time fan of folklore and cultural stories, and with a fair amount of Norwegian blood (ancestors from Norway and Viking genes via my Cornish family history as well), I was delighted to have a copy of this new translation of Norwegian folktales. Having read such tales from childhood on, I’ve often been amazed at the similarity of such stories across cultures, often those with no connection to each other over the times when such tales were told from one generation to the next, in terms of theme, moral lessons, and plots. I heard echoes of Anansi (East Africa), Grimm and Anderson (Western Europe) and Native American tales and more in these stories. We are truly diverse as a human race, but we are more alike than some people would care to admit. All have heroes and villains, magic and quests, poverty to riches, and the poor one outwitting the king/chief.

As a long-time fan of folklore and cultural stories, and with a fair amount of Norwegian blood (ancestors from Norway and Viking genes via my Cornish family history as well), I was delighted to have a copy of this new translation of Norwegian folktales. Having read such tales from childhood on, I’ve often been amazed at the similarity of such stories across cultures, often those with no connection to each other over the times when such tales were told from one generation to the next, in terms of theme, moral lessons, and plots. I heard echoes of Anansi (East Africa), Grimm and Anderson (Western Europe) and Native American tales and more in these stories. We are truly diverse as a human race, but we are more alike than some people would care to admit. All have heroes and villains, magic and quests, poverty to riches, and the poor one outwitting the king/chief.

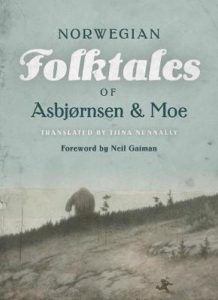

What differentiates each culture’s tales are the people themselves and the geography of each area. Neil Gaiman points out in his Foreword that there is a focus on the chill in Norwegian tales. Deep dark forests, tall mountains, crevices and fiords. The characters come to the stage in a way that engages Norse mythology—shadows of forest giants echo Thor and Loki. “Our sacred mysteries become myths, become folk tales, and forest giants and gods become trolls and heroes given enough time.”

Another part of folk tales I’d never considered before is the aspect of translation. The original collectors, Asbjørnsen and Moe were highly educated men. The first being a scientist of biology and zoology and a writer, while Jørgen Moe was a farmer and land owner from a prominent family. The story tellers, however, were simple country people chatting by the fireside. The collection of tales began in 1827 and lasted until the third published edition in 1866. While the two story collectors preserved the original style of speaking, the translator has the job of taking that into another language and some words don’t translate well. There must be a balance between “literal” translation and keeping the deeper meaning. In several stories, there are statements in first person by the narrator that make you feel as if you are sitting in that room by the fire while some family patriarch spins the tale on a cold winter evening. Reading through the translator’s notes gave me a whole new appreciation for Tiina Nunnally’s task. Readers should not skip over the Foreword and Translator’s Notes.

Even within one culture, stories can vary. There are several stories in which Ash Lad is the hero. Sometimes he’s the youngest of three sons, in others there are seven or even twelve brothers. But he’s always the youngest, always the underdog who manages to come out on top. Considered a lazy fool, he’s really intelligent, a trickster and a planner at the same time.

The stories contain lots of ships and storms, talking animals, and elements of other Western European fairy tales but with unique Norwegian twists. A reader never knows if a troll will be friendly and help the hero or whether it will try to eat him—many stories don’t follow a “standard” script. This leaves readers wondering what will happen from one to the next. Trolls often have a flask (which heroes steal) which heals all injuries and sometimes even brings people back from the dead. Others have great humor, especially “Some Women Are Like That” and another in which the man of the house trades jobs with his wife and finds out keeping house isn’t that easy! This theme probably echoes in every era and culture. There is also humor in “Paal Next Door” in which readers find a good bit of cheating going on between the wife and Paal.

“The Three Aunts” reminds us to do what you promise, while “The Widow’s Son” and “The Husband’s Daughter” moralize about being kind, following directions, and that ever-present “what goes around comes around.” Another story, “The Virgin as Godmother” provides a theme of suffering and redemption. The sly person getting “one up” on others comes through in “The Blacksmith They Didn’t Let into Hell” and “The Master Thief”, which add some con artist humor.

Unique similes abound in descriptions: “His voice was as pitiful as a two skilling coin”; the road “so flat you could roll and egg along it”; and “as lightly as a pea on birch bark.” In several stories, the same dialogue and events are repeated three or more times, which probably made the stories easier to memorize for oral story tellers.

One could spend a lifetime analyzing themes of faith, morality, always do the right thing, be honest, etc. along with myths of how things came to be, all of which are typical of every culture’s folk lore. Norwegian Folktales of Asbjornsen and Moe is the kind of book you can pick up and put down over several weeks (between other types of reading) and always end up smiling. Pick up a copy and don’t miss out.

University of Minnesota Press, 2019, ISBN 978-1-517905-68-2, hardcover, $34.95

About the Reviewer

Deborah K. Frontiera

Deborah K. Frontiera grew up in Michigan’s Upper Peninsula. From 1985 through 2008, she taught in Houston public schools, followed by several years teaching in Houston’s Writers In The Schools program. A “migratory creature”, she spends spring, summer, and fall in her beloved U.P. and the dead of winter in Houston, Texas, with her daughters and grandchildren. Four of her books have been honor or award winners. She has published fiction, nonfiction, poetry, and children’s books. She edits the newsletter for the Upper Peninsula Publishers and Authors Association. For details about her many books and accomplishments, visit her web site