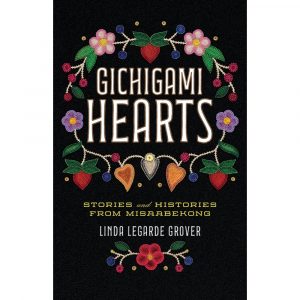

New Book Weaves Together Ojibwe, Duluth, and Family History

Gichigami Hearts: Stories and Histories from Misaabekong by Linda LeGarde Grover is a potpourri of Ojibwe legends, family history, and regional history all interconnected to ask questions about what it means to be Ojibwe, to live in Duluth, to grow up Ojibwe in an Italian neighborhood in Duluth, and to tell stories about oneself, one’s people, and one’s homeland.

Gichigami Hearts: Stories and Histories from Misaabekong by Linda LeGarde Grover is a potpourri of Ojibwe legends, family history, and regional history all interconnected to ask questions about what it means to be Ojibwe, to live in Duluth, to grow up Ojibwe in an Italian neighborhood in Duluth, and to tell stories about oneself, one’s people, and one’s homeland.

Grover is also the author of the novel In the Night of Memory, about Ojibwe women who disappear from their communities, which has previously been reviewed here. This time, however, she writes nonfiction, or rather creative nonfiction, for while her personal and family stories are true, they are interwoven with legends and Ojibwa magic to create a narrative that might well be described in places as magical realism.

The bulk of the book is about the Duluth area and Grover’s Ojibwa heritage from growing up there. The “Gichigami” in the title refers to Lake Superior while the “Misaabekong” in the subtitle means “the place of the giants” and refers to the rock outcropping in Duluth. Grover shares some of Duluth’s history, including that it was named for Sieur du Lhut, who arrived there in 1679, but she also notes her own people, the Anishinaabe, were there generations earlier. The family history she records covers the last two hundred years as she discusses how her ancestors moved about, especially after the 1854 treaty that gave their land largely to the Americans. Among the memorable events of her family’s past is that her three-great-grandparents were married by the famous Bishop Baraga, as well as family stories she records from older family members, including her uncle Bob, who was born in 1912 and the last member of the family who spoke fluent Ojibwe.

Grover grew up in Duluth in the 1950s and 1960s. She recalls the places her family members lived then and what life was like at the time, from growing up in an Italian neighborhood, to the other ethnic neighborhoods in the cities, how people would dress up to go downtown, and memories of her grandfather, including fifty years later, reminiscing about him with a woman her age who had once been part of a family that had cared for him in his later years.

Blended with all this city and family history are stories of the Ojibwe and even poems. Tales exist of Nanaboozho, the great trickster of Ojibwe legends, of Lake Spirits and the Great Flood, as well as stories about the Windigo—creatures who crave flesh and how to kill them—and the tale of how when blasting a large rock in Duluth many years ago, it split in two and an Anishinaabe man in traditional clothes stepped out from the fissure.

As a lover of family history and regional writing, I found a lot in Gichigami Hearts that appealed to me, and I only wished I knew Duluth better so I could appreciate it more. However, what perhaps most deeply resonated with me were Grover’s philosophical moments, when she asks questions such as why some Ojibwe have been luckier than others. At one point, she even includes a manifesto of Ojibwa philosophy. Throughout, she is appreciative of the past, her ancestors, and their influence on her life. She states:

“I have lived my life against the backdrop of my ancestors and the histories and events that determined how they would survive and our family continue. Vast in experience and time, in tangibles and intangibles, in a spirituality and presence mysterious and yet so simple, from the other side that is not really another side at all, they move and breathe with me, and I with them.”

Later, she talks about the Ojibwe perspective of history:

“Indian family histories are collective and complex, walked by ghosts of past, present, and future bearing forged chains that can rattle and clank painfully when shaken, sometimes by what might appear outside of Indian Country to be the most innocuous of questions.”

Questions are also raised about who owns history—who owns the past. In speaking with her grandfather’s former caretaker, Grover wonders who owns her grandfather’s story, and she decides not to write the parts of it that the caretaker lived and therefore belong instead to her. In connection with this is the subtle theme of telling stories and history to preserve it for the future. She asks permission of relatives to write down their words. She also recalls family members who sold “tourist art” at roadside stands—tourist art being Native American items created with the intent to sell them to tourists; even though commercially made, these items are also handmade so they have cultural, historical, sociological, and spiritual aspects to them beyond what individuals can see or feel. All these topics reflect various ways to preserve the past and ensure Ojibwe stories and culture live on.

I have read many books about the Ojibwe, but Gichigami Hearts really gets to the heart of how the Ojibwe mind thinks in terms of the past, present, and future, and what it means to be Ojibwe—what it means to tell that story about that way of being. Anyone from the Duluth area or interested in Native American studies will find this book worth exploring.

— Tyler R. Tichelaar, award-winning author of Kawbawgam: The Chief, The Legend, The Man