Marquette Poets Circle’s Newest Book Is Superior

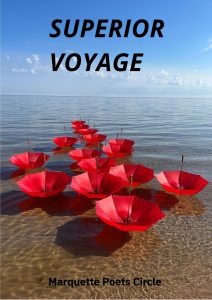

Five years ago, the Marquette Poets Circle wowed readers with their debut poetry book, Maiden Voyage. Their follow-up volume is titled Superior Voyage, and it is appropriately titled for it is a superior volume of poetry that just happens to have been written near Lake Superior, though the magic of Lake Superior informs many of the poems. As Lynn Domina writes in her poem “McCarty’s Cove”:

Five years ago, the Marquette Poets Circle wowed readers with their debut poetry book, Maiden Voyage. Their follow-up volume is titled Superior Voyage, and it is appropriately titled for it is a superior volume of poetry that just happens to have been written near Lake Superior, though the magic of Lake Superior informs many of the poems. As Lynn Domina writes in her poem “McCarty’s Cove”:

This afternoon, as winter shifts finally

toward spring, I wouldn’t have imagined myself,

still barely believing my luck, kneeling

in sand between the lighthouse keeper’s red house

and the cove surely meant for swimming,

filling my cupped hands

with fresh water, remembering here,

I live here.

We in the U.P. can barely believe our luck that such a fine array of poets live here.

Like Maiden Voyage, the book is a compilation of poems from numerous members of the Marquette Poets Circle. It is impossible to list all the poets or even comment on one fine poem from each member, but many of these names will be recognizable to local poetry lovers, including two-time UP Poet Laureate Marty Achatz; Janeen Pergin Rastall and husband Richard Rastall, who are not only great poets but wonderful promoters of poetry and central to this book’s publication; five winners of the City of Marquette Writer of the Year Award: Beverly Matherne, Russell Thorburn, Kathleen Heidemann, Janeen Pergin Rastall, and Milton Bates; two posthumous members, Genean Granger and Bert Riesterer, to whom the book is dedicated; Helen Haskell Remien, who also passed away just before publication; and Matt Maki, a founder of the Marquette Poets Circle. New voices in this volume include Gideon Achatz, the teenage son of Martin Achatz.

As for topics, not surprisingly, many of the poems are influenced by nature and the beauty of the Upper Peninsula as well as the difficulties of living here, especially in winter. Several poems were written during the pandemic and reference it. But other poems cover a variety of topics ranging from Bigfoot and war to romantic love, family relationships, and dinosaurs. I will mention briefly a few of my favorite poems and apologize to all the poets whose works are not mentioned here.

Perhaps the poem that most pulled on my heartstrings was “For My Grandchildren” by my late friend Helen Haskell Remien. Helen adored her grandchildren; I never saw such an enthusiastic grandmother, and so this poem she wrote is all the more poignant now that she has passed. She begins:

You will never be alone

that’s what I want to tell you

even when you wake up in the middle of the night

and your fairy light is broken

and your room is really dark

not even then

The poem goes on in this vein listing times they won’t be alone until it tells the grandchildren to stay still for a moment,

and you will remember you are always

here for yourself

and you, dear one, are your own best friend.

Christine Saari also writes about her grandchildren. Saari grew up in Austria during World War II and her Austrian heritage and past often seep into her poems. In “Dollhouse,” she describes how she built a dollhouse for her four-year-old granddaughter as she listened to all the news coverage following 9/11. Then she compares it to how when she was four, the Polish man who was a forced laborer on her family’s farm during World War II built her a dollhouse, even though she was the daughter of his enemies. As the poem progresses, Saari’s granddaughter grows up, but she remains able to find comfort amid the world’s chaos in her miniature world.

Another moving poem is Martin Achatz’s “Ascension,” in which the poet writes about his late sister Rose, feeling how deeply important she was to him, comparing her to Jesus and himself as one of her disciples, concluding,

I could spend the rest

of my days writing gospels and gospels

about how much you loved me.

John Taylor surprises the reader with two quirky imaginative poems. In “The Damned Monsters,” he compares our childhood fear of monsters to the dictators and other real-life monsters in the world today, stating we were safer with the childhood monsters. Then in “The Dinosaur’s Horoscope,” he imagines the destruction of the dinosaurs by meteors and wonders if the mother Maiasaurus looked up at the sky and sang “Twinkle, Twinkle Little Star,” to her young, not knowing the shooting star would doom them. According to Taylor’s bio in the book, he is on the autistic spectrum. This fact influences the poem he cowrote with his wife, Miriam Taylor (who has her own fine poems included in Superior Voyage). In their shared poem, “My Hand in Yours,” I enjoyed the devotion and gender role reversal. The poem begins by stating:

Being married with a disability means The other half

Of your heart can be half of your mind and body, too

Learning your loves’ strengths and your weaknesses

Is the key to a world of wonder through grief…

The poem repeats the line “The princess rescues the knight” and then concludes by stating:

The Strongest tool in your hand is always another hand

The Path may be rocky, but it’s all about the hand we hold…

Perhaps the eeriest poem in the book is Robert Polzin’s “Chute 13.” It reminded me of the classic “Goblin Market” by Christina Rossetti. Here it is not goblins but the voices of dead children that entice the speaker. They want him to come play on top of the ore dock and join them in Chute 13, which will certainly mean his death if he follows through.

Some poems are quite literary, drawing upon famous poems for their themes or structures. Kathleen Heidemann’s “Evidence of Deep Negaunee” depicts two people moseying through Negaunee, then crawling beneath a barbed-wire fence into the caving grounds. The stanzas repeatedly borrow from famous poems for their voice. If one reads carefully, they will note the words or style of Dylan Thomas, Robert Frost, Walt Whitman, and the Lord’s Prayer woven into the work. Her poem “Miracle in the Museum of Iron Industry” evokes Auden’s famous poem about suffering, “Musee des Beaux Arts,” which begins, “About suffering they were never wrong,/The old Masters: how well they understood.” Heidemann begins her version as “About rusting they were never wrong,/our deep-shaft miners: how well they knew/the holy mystery of oxidization.”

Aging is also a topic in some poems. Gala Malherbe’s poem “Family Reunion with Aunt Pauline” describes a summer picnic with her 104-year-old-aunt who can recall when the tall pine trees were shorter than she is now. Malherbe compares their family tree to that of the white pines. Genean Granger’s “Pity Party” describes the difficulties of growing old and having health problems. Children point at her as “I pull a can of oxygen behind me/like a dead dog.” She feels “disregarded” and “invisible” even though she is more pleasant than many who walk in her world, and she concludes:

I’m funny and smart. I’ve been desired, wedded

and bedded. Now, I’m seen as damaged,

less than someone who’s whole.

Political and social issues also get their space in this volume. Matt Maki, who lives in Ukraine now, shares “Not Beautiful,” which he dates “24th February 24, 2022 8th year & 1st day of war” (a surprising date for those who think the war in Ukraine only started on that day). Maki writes, “I’m sorry this isn’t a beautiful poem,/but what have you done to deserve something beautiful?” He tells the reader the war started eight years ago but no one paid attention and:

A slow local news day is the only reason

you’re paying attention now: it’s either this

or a new Supreme Court judge.

So no, you haven’t earned something beautiful.

You barely even deserve the truth,

but that’s what I’ll give you here nevertheless.”

Lynn Domina’s “Chant to Lift Up the Soul of George Floyd,” ties Floyd’s death to our own feelings that we can’t breathe. Erin Anderson’s “American Streets” discusses how she felt invisible in a US apartment in what appeared to be a concrete box so she went back to Central Europe with its turrets and onion-domed spires where there was “Pretty stuff with no purpose.” Carolyn McManis’s “White Privilege” discusses how mothers know the truth, that “Our children are not equal in this land.”

Winter leaves Troy Graham in “A Winter’s Poem” asking “Where are you humanity?” Claudia Drosen writes “a fantasy” poem about “Parking Lot Snow Piles: Upper Michigan,” and Russell Thorburn’s “Cold Snap” perfectly captures those below-zero-degree days we all know too well.

Many other poetic treasures fill this volume. In “The Gift,” written in memory of her partner Roger Magnuson, Beverly Matherne discusses how “I hold you in a meadow of trillium, in Munising.” A surprising number of prose poems are included by John Gubbins, Jesse Koenig, and Jane Piirto, which may well appeal to the reader for whom poetry is not a favorite genre. Finally, Roslyn Elena McGrath delights us with her instructions for “How to Find a Poet.”

If you want to know how to find a good poem, you need look no further than Superior Voyage. These poems, like shiny Lake Superior pebbles, are just waiting to be discovered.

— Tyler R. Tichelaar, award-winning author of My Marquette and Kawbawgam: The Chief, The Legend, The Man

Superior Voyage

Marquette Poets Circle

Gordon Publications (2022)

ISBN: 978-0-9857127-6-1

Wow thank you Tyler. I am so glad you enjoyed the book and the variety of voices.

Thank you for this thoughtful, detailed review accentuating myriad poetic voices in the U.P., Tyler. It is a beautiful collection, and I’m proud to be a part of it.