Review by Deborah K. Frontiera

Niiji, A Collection of Poetry is a unique “own voices” work that highlights two poets whose styles are different yet blend in their approaches to the theme. Sally Brunk sets the tone early on with her poem, “Authority Figures”, in which she states:

Niiji, A Collection of Poetry is a unique “own voices” work that highlights two poets whose styles are different yet blend in their approaches to the theme. Sally Brunk sets the tone early on with her poem, “Authority Figures”, in which she states:

“The intellectuals think it’s fascinating, interesting to be ‘Indigenous’,

I’m looked upon as a specimen, a rarity, a lab rat, . . .

But come to the res, find it for yourself, . . .

Ask them all, every question that fills your book,

You may learn, but will you UNDERSTAND?”

Which is followed a few pages later by Ron Riekki’s section of poems writing from the point of view of a person who, all his life, thought he was Finnish and discovered after a DNA test that he is of the indigenous “Saami” people—the reindeer herders of the far polar regions who are more “Native” than “other Finns”. In his poem “My Saami Roots”, he ends with one word, “hurry”, to prevent the extinction of his people. His poems dwell on that theme of the powerful committing genocide upon weaker people in order to promote their own superiority. His poems are a cry of anger and frustration against the constant injustices that all “Native” people have experienced.

Ron Reikki also expressed the conflict of trying to be a regular person and be his “own voice” at the same time, and his coming to grips with who he really is. In all this, is a longing for true inner peace and the desire to feel less alone. Several of his poems reveal that conflict in the “secret” stories told to him by his grandfather and others that he really is Saami, but no one should know that, because he might be killed for it. In other words, deny who you are to preserve yourself. He also criticizes “forms” that ask you to reveal your race but leave no place for biracial entries.

In “Elegi to the Saami”, he says there is “an aurora borealis in our will to survive”, which is followed by a pointed essay, “Asse (Saami for skin)”, where he speaks of finding himself. Another interesting poem is “Song of the Suffering of My Liver”, where rhyme and rhythm give way to near rhyme and less rhythm, followed by some dark free verse. Does this refer to his own inner conflict? But later, we find a reason: “There are so many poems about clouds because clouds are swallowed as easily as water.” To this reviewer, that expressed the conflict he felt and the conflict people felt when they saw him as “too white to be indigenous”.

On the other hand, Sally Brunk’s poems stress our commonality rather than our differences. “In Celebration of Women”, while it emphasizes Native American women and traditions, speaks of all women holding up the earth. Her themes of the cycle of life and death, birth and new generations speaks to the human condition. How many generations of women have been “stuck” in a rocking chair with a sleeping baby? Brunk’s expression of grief over the deaths of her sister and father touch all people on the earth, even if they have different funeral and burial traditions. While reading “All My Relations” preparing for the drums and dance, one can’t help but wonder: Is it not the same process as the Irish teaching their children a jig, another family teaching their young ones to polka? Family is family, and families pass their culture down through the generations. There is richness in the diversity of human culture as well as in each tradition itself. And every culture deserves to be celebrated and preserved.

Are guardian spirits any different from guardian angels? Or the thought on page 89:

“There is no time; there is only existence,

There are no boundaries, no color lines,

It is as one circle.

As the Creator says it should be.”

But Brunk does not ignore the tougher questions. Many of her poems also speak of the injustices and prejudices we hold toward people “not our own;” and how the Keweenaw Bay Indian Community must now fight to save its culture as more and more young people turn away, or turn to drugs and alcohol, resulting in abuse and poverty because of the loss of traditional culture. She also points out how the “Christians” abused Native children in their efforts at “boarding schools” to indoctrinate the young to “become White.”

Between the two poets, Riekki stresses the anger, resentment, injustice, genocide, and “darker” themes, while Brunk reminds us all that while we may have different languages, customs, religious beliefs, skin colors, and body types, we should remember that we are all human in terms of family, love, grief, joy and sorrow.

The title word Niiji is never defined, but I did some research and found it is an Anishinaabek word that replaces the old misnomer “Indian” for aboriginal people. This collection deserves reading, pondering, and rereading over and over.

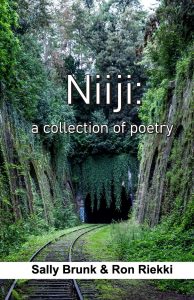

Niiji, A Collection of Poetry

Publisher: Cyberwit.net,

Pub Date: 2020,

ISBN 978-93-90202-36-2,

Retail $17.00

About the Reviewer

Deborah K. Frontiera

Deborah K. Frontiera grew up in Michigan’s Upper Peninsula. From 1985 through 2008, she taught in Houston public schools, followed by several years teaching in Houston’s Writers In The Schools program. A “migratory creature”, she spends spring, summer, and fall in her beloved U.P. and the dead of winter in Houston, Texas, with her daughters and grandchildren. Four of her books have been honor or award winners. She has published fiction, nonfiction, poetry, and children’s books. She edits the newsletter for the Upper Peninsula Publishers and Authors Association. For details about her many books and accomplishments, visit her web site