Review by Victor R. Volkman

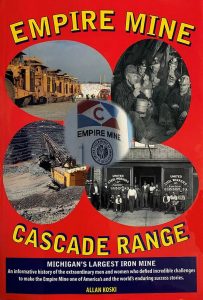

Allan Koski is that rare combination of an eloquent historian, talented engineer, and a storyteller with a penchant for seeing the big picture. Because I thoroughly enjoyed Koski’s Another Time, Another Place: World War II in the Pacific 1941-1944, which details the exploits of his father Eino Koski in the Navy Catalina PBY-5 “Flying Boats”, I was thrilled when Empire Mine Cascade Range: Michigan’s Largest Iron Mine crossed the review desk. In this book, Koski literally leaves no stone unturned to provide both a history of iron extraction in the Upper Peninsula as well as a nearly day-by-day account of the struggles of the Empire Mine and other Cascade Range operations

Allan Koski is that rare combination of an eloquent historian, talented engineer, and a storyteller with a penchant for seeing the big picture. Because I thoroughly enjoyed Koski’s Another Time, Another Place: World War II in the Pacific 1941-1944, which details the exploits of his father Eino Koski in the Navy Catalina PBY-5 “Flying Boats”, I was thrilled when Empire Mine Cascade Range: Michigan’s Largest Iron Mine crossed the review desk. In this book, Koski literally leaves no stone unturned to provide both a history of iron extraction in the Upper Peninsula as well as a nearly day-by-day account of the struggles of the Empire Mine and other Cascade Range operations

Starting with the revelation of iron ore in the U.P. by Marji Gesick, the Native American guide, the author gives us a detailed look at the early days of mining. Koski’s overview of the life of an underground miner is stark and eye-opening. For example, he shows us the progression of lighting in the mine from candles attached to the miner’s caps to battery powered lamps and finally electric lights. The dangers of making a wrong turn underground and taking a hundred foot fall down a shaft are illustrated with accounts from the local newspapers. Children falling into disused pits and the subsequent remediation are another tragedy that had to be mitigated. Indeed, the archives of The Mining Journal are the basis for much of the coverage of strikes, their negotiations, and resolution which dominate about a third of the text.

Allan Koski comes by his knowledge of the Empire Mine and Cascade Range honestly. He definitely started at the bottom as a general laborer working his way through college in the mid 1960s. Koski graduated from Michigan Technological University with a degree in Mining Engineering in 1969 and so was that rare guy whose experience spanned both the rank-and-file and the management team. Indeed, he retired as Senior Staff Engineer after 44 years on the job at Empire Mine. Additionally, he has been instrumental in helping preserve industrial history in his 20 years of service on the Board of the Michigan Iron Industry Museum.

As most yoopers probably know, the Empire Mine was run by the Cleveland Cliffs Iron Company and was shuttered in 2016. After more than a century in operation as a strip mining site, it remains the biggest hole in the ground east of the Mississippi river. It is 1.5 miles wide and 1200 feet deep, the volume of which is undoubtedly greater than many of Michigan’s smaller inland lakes. As a young lad growing up in Grosse Pointe Park, Michigan in the early 1970s, I would often see what seemed like an endless chain of lake freighters hauling ore downbound on the Detroit river which was barely a thousand feet wide from the vantage of Patterson Park. Little did I know that the 858 foot MV Roger Blough was hauling iron from the Empire Mine literally within a stone’s throw of the dock where I stood.

The book is organized, for convenience, by decade with a general theme for each ten year span from decades starting in 1930 to 2010. Empire Mine Cascade Range is unparalleled in its photographic record of daily operations, strikes, and celebrations. Each chapter ends with a glossy photo section and the photos from the last 40 years are generally full-color reproductions. Koski is able to draw photos from local newspapers, Cleveland Cliffs archives, and local US Steelworkers Association (USWA) newsletters for the most comprehensive documentation I believe the world will ever see of the area.

For me, the most exciting aspect of the book is the massive Apollo-era engineering that went into the modern Empire Mine. Some of the goals that they managed seem as fantastic to me as a moonshot. It all revolves around the new technology of pelletization to allow American steel to compete with the foreign competition that was already taking a full one-third of the market share by 1960. The list of technical and logistical challenges is stunning: a state highway had to be relocated, a dam built to create a reservoir for the plant, and Michigan’s first autogenous grinding system had to be invented. Autogenous means the ore is grinding itself in a big cylinder to eventually get down to a fine dust that can be turned into pellets. This process was the first of its kind in America and the first two-stage autogenous grinder in the world. At the end of the line was a massive kiln for firing the pellets into shape. The kiln was 115 feet long, 18-1/2 feet in diameter, and weight 225 tons. Delivering the kiln required a logistical effort equivalent to transporting the first Space Shuttle. Now, the site preparation for strip mining was another achievement—2.5 million cubic yards of earth was excavated and used to construct a railroad grade 50 feet high. Empire Mine phase I was a huge success and had the biggest Return on Investment (ROI) of any mine anywhere in America at the time!. The production goal of 1.2 million tons of pellets per year was easily achieved and over the next 20 years would quadruple with Empire II, III, and IV coming online eventually.

There’s a lot more to Empire Mine Cascade Range that I can put down in this brief review. I would recommend this book in any curriculum of Michigan state history as well as for a graduate course in labor relations. Koski’s book is now the definitive text on the history of iron mining in Michigan and it should be a source of pride for four generations of yoopers who worked the Empire Mine which sourced the raw materials for America’s cars, skyscrapers, and even iron ore freighters themselves. Enlivened by rare photos, it paints a complete picture from mine workers to management. Available at local stores including Snowbound Books.