Review by Deborah K. Frontiera

Throughout human history, stronger civilizations have taken over weaker or indigenous peoples and have then attempted to erase their existence after claiming anything of value. Yet, many of these cultures managed to endure, redefine themselves and, often, demand their culture, artifacts, and rights be returned to them. This pattern of conquer/subjugate and erase was particularly true of Western European nations as they colonized other continents from the 1500s on. In its March 2023 issue, National Geographic’s feature article dealt with the subject of returning treasures taken from ancient Egypt, Greece, and various African countries to their nations of origin.

Throughout human history, stronger civilizations have taken over weaker or indigenous peoples and have then attempted to erase their existence after claiming anything of value. Yet, many of these cultures managed to endure, redefine themselves and, often, demand their culture, artifacts, and rights be returned to them. This pattern of conquer/subjugate and erase was particularly true of Western European nations as they colonized other continents from the 1500s on. In its March 2023 issue, National Geographic’s feature article dealt with the subject of returning treasures taken from ancient Egypt, Greece, and various African countries to their nations of origin.

This pattern of colonization and the sending of Christian missionaries to convert native peoples, followed by repression of those peoples and the “collecting” of their artifacts and culture occurred within Europe, too. That is the subject of Barbara Sjoholm’s book about Sápmi (Lapland) and the indigenous Sami people of northern Norway, Sweden, Finland, and Russia. The author describes how the artifacts and culture of the reindeer herders of the tundra and mountains and the “sea” Sami fishing cultures of the northern Norwegian coastlands were “collected” by missionaries, merchants, and scientists and then taken to museums in Copenhagen, Stockholm, Oslo, cities in England and Germany, to exhibition halls world-wide and even to zoos!

In the author’s introductory comments, she states, “My aim here is not a comprehensive history of Sápmi over the past four hundred years. Instead, each chapter in Parts I and II takes on a time period and a series of events and personalities to create a narrative around one or more collections—of religious objects, of ethnographic artifacts, and of shifting assemblages of art, music, and craft.”

One example is the Sámi ceremonial drum, which for the Sámi was a way of teaching understanding, “a solace and a compass.” Drums were passed from one generation to the next and carefully wrapped in furs when not in use. But Christian missionaries considered the drums an evil “idol”, often confiscating them from their owners under pain of death and forced conversion to Christianity.

“Ripped, smashed, and burned in bonfires, hundreds—perhaps thousands—of drums vanished over a period of about a hundred years, from the early seventeenth century to the first decades of the eighteenth century.” (pg. 11)

Drums that survived were often sold by missionaries and others as “curiosities”, ending up in the possession of the wealthy, kings, queens, and others, a few of whom with better intentions gave them to museums. Scholar/scientists who acquired them at least had the sense to preserve them, or there might be none anywhere today. The story of how one particular drum changed hands several times, with all the names and reasons for its transfer from one person to the next fascinated me.

In another chapter, an ethnographer named Professor Friis linked up with a young Sami man named Lars Haetta and some of his friends who had been imprisoned for a rebellion of the Sami in the mid-1800s. Friis had many conversations with this young man, who carved models of much of Sami life—everyday objects, animals, Sami camps—explaining Sami culture. Friis, for all his good intentions, certainly did profit from what he learned by writing several books. Friis even wrote a novel based on the experiences of two of the prisoners which was ultimately made into a movie in 1929, Laila. A poster for this movie and some of Lars’ miniatures are pictured in color in the illustrated plates section of the book between pages 189 and 191.

A particularly interesting chapter involved a man named Karl Tiren who used the early wax cylinder phonograph process to record Sami singing, “joiks” and “joiking”, as well as stories of life. The hundreds of wax cylinders are preserved and can still be played and heard! Another favorite chapter involved a “love story” of sorts between Emilie Demant and John Turi. Emilie was staying with a Sami family studying their way of life. While Emilie liked John, he fell in love with her, giving her a beautiful blue “giisa” a small oval chest made of wood and bark, carefully decorated and painted. Such chests were used like small suitcases. Although Emilie married another man, she kept that box for many years, ultimately giving it to the Nordic Museum of Stockholm, Sweden. John never quite got over her.

The motivations of the many scientists, ethnographers, and others who collected Sami artifacts and culture range from the desire to preserve to exploitation and outright theft, and sometimes the “real people” behind the objects and art were left behind. But the fact that people collected for any reason did preserve a great deal of Sami culture, which Sami in the northern areas of Norway, Sweden, Finland, and Russia are now actively “recollecting”, bringing home and reintroducing to their own people today.

As I read the book, several parallels to American colonialization by the British, and the treatment of Native Americans by both the English and the Americans occurred to me. First, a colony is set up to benefit the “mother country” economically. The “mother country” invests in an area, exploits any natural resources, and generally disrupts the lives of people already in that area—usually with little regard for those people. The “theme” is to move in, take over, get what you can and leave the damage behind. This happens internally as well. With the Scandinavian countries, they went for the minerals and forests, forcibly taking land from the Sami. British and then later Americans did the same to Native Americans. Wealthy businessmen of the USA east did something similar to many parts of Michigan’s Upper Peninsula—ship out the iron and copper, cut all the trees to benefit their businesses, often not building up the area they “colonized”. Second, Witchcraft Trials of Sámi men and women occurred around the same time as the Salem, Massachusetts Witch Trials. Third, the exhibition of native skills, art, and shows of everyday life were merely entertainment for the curiosity of others. Natives make art for tourists, not for art or utilitarian sake. Finally, Norway had a program of “Norwegianization” of Sami children—boarding schools, etc. Sound familiar?

The third section of the book deals with how Sámi people are reinventing themselves, demanding their rights, passing their ancient and newer culture on to new generations and the complexities of doing all that when they live in four different modern nations. Part III has an interesting discussion of the directions these efforts might take. While there were a few places where I got bogged down by the length of a chapter (perhaps because it was at the end of a long day) overall, there is much of great interest that readers can learn from this book.

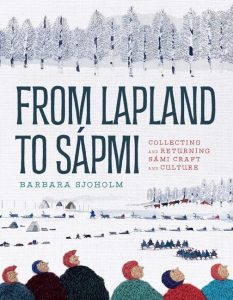

From Lapland to Sapmi

By Barbara Sjoholm

University of Minnesota Press, March 2023, ISBN 978-1-5179-1197-3, Ret. $34.95 cloth/jacket